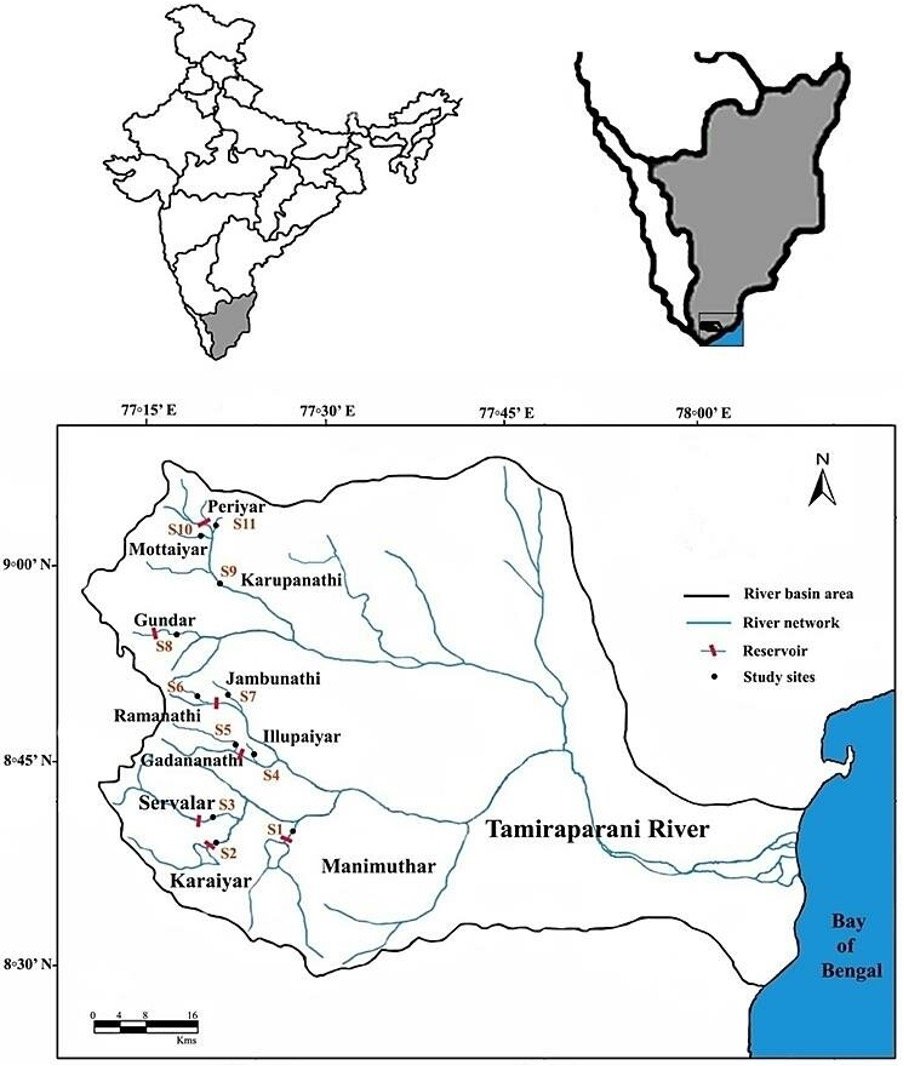

Lassen in his Indische Atterthumskunde (Vol. I) describes the Tamraparnl as "an inconsiderable stream, with a renowned name." Looking at the length of its course (only 70 miles (112 Kms) from its rise to the sea, including windings), it may certainly be considered an inconsiderable stream, but it holds a high position amongst the Indian rivers in regard to the benefits it confers ; and its name seems to have become famous in India from a very early period. It may worthily be called an "ancient river", by which we understand a river renowned in ancient song. It is mentioned amongst the rivers of India in the geographical sections of several of the Puranas, and seems to have been regarded in those times as a particularly sacred stream. It is represented as rising in the Tamra mountain also known as Malaya, and this enables us to identify Malaya with the Mahabharata’s Southern Ghats.

Tamraparṇi (ताम्रपर्णी) — A sacred river of southern Kerala (Dakṣiṇa Kerala). According to legend, the Devas once performed penance on its banks to attain salvation.

(Refer: Sloka 14, Chapter 88, Vana Parva, Mahabharata)

One of the earliest and most significant references to the river in Sanskrit literature appears in the Mahabharata:

Tamraparṇi (ताम्रपर्णी) is the name of a sacred river mentioned in the Sivapuraṇa (1.12):

Somehow, men must strive to find residence in a holy centre. On the shores of the ocean, at the confluence of hundreds of rivers,

there are many such sacred centres (puṇyakṣetra or tirtha) and temples.

Tamraparṇi (ताम्रपर्णी) — The name of a river that originates from Malaya, a sacred mountain (kulaparvata) in Bharata, as mentioned in the Varahapuraṇa, Chapter 85.

There is an interesting, though probably much later, verse in the Raghuvamsa, in which the Tamraparni is mentioned. Raghuvamsa says,

Tamraparṇi (ताम्रपर्णी) — According to Sri Caitanya-caritamṛta, Madhya-lila 9.218. In the Ramayaṇa the name of Tamraparṇi is mentioned. Tamraparṇi is also known as Puruṇai.

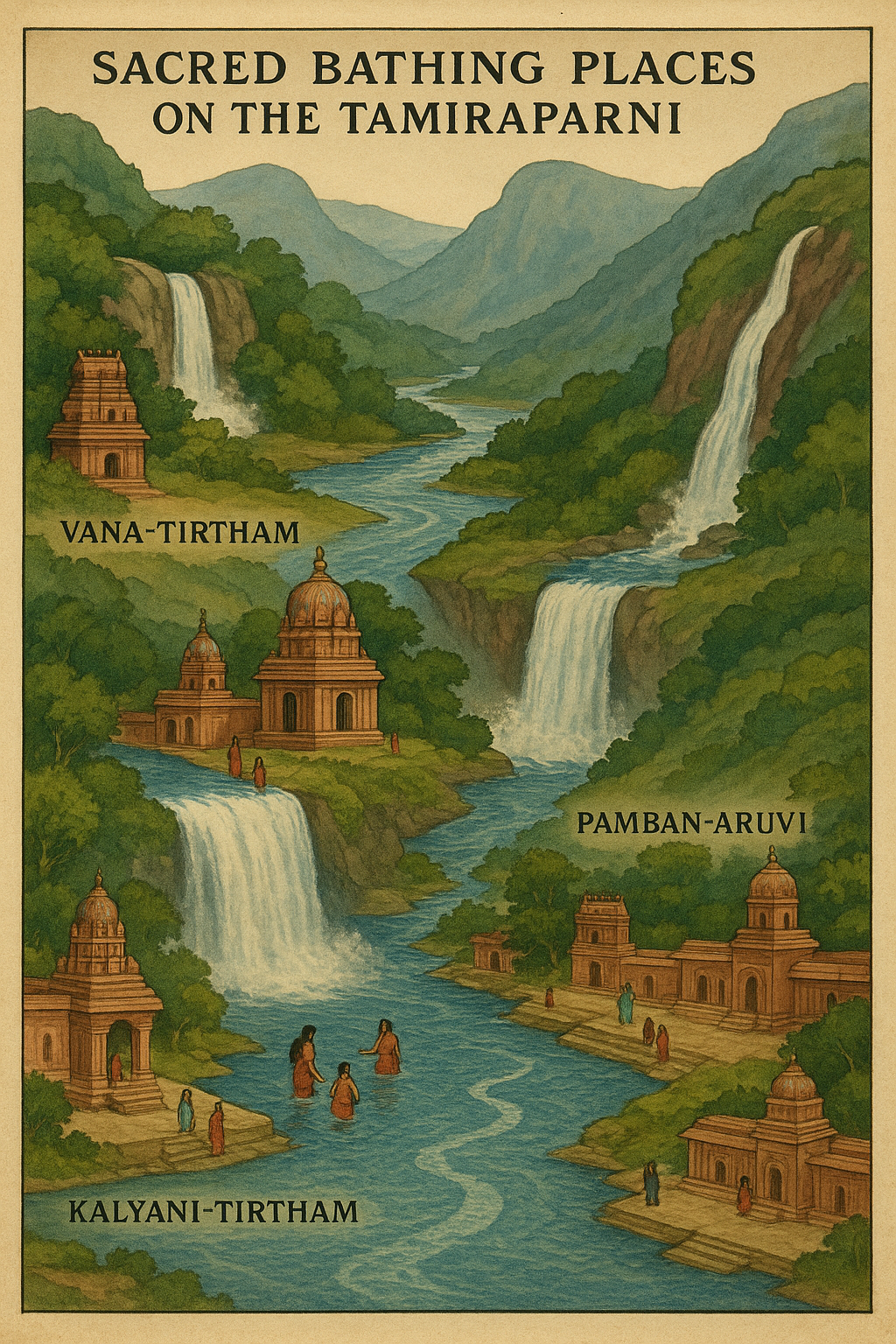

There are two of these waterfalls on the main stream, one called Vanatlrtham (from the name of an Asura called Vana) on the slope of Potiyaru, and another still more frequented, about 90 feet in height, at Papa-nasakani (Papanasam) (destruction of sin). The latter is commonly called Kalyanitlrttam, the sacred bathing place of Kalyani (Parvati), but by some Kalyana-tlrtham, the wedding bathing place, that is, the place where Parvati's marriage to Siva was exhibited to Agastya. This fall is at the place where the Tamraparni leaves the mountains and enters the plains. There is another celebrated waterfall, not far from Vana-tirtham, called Pamban-aruvi, the snake waterfall, so-called on account of its long snake-like appearance when seen from a distance. It consists of two falls, the upper 500 feet in height, the lower 200 feet. This remarkable fall is not on the main stream, but on a tributary, which rises on the " five-headed Potigai." Temples adorning the banks of the river have “Padithurai” and the river is blessed with 147 such places for devotees to bathe.

The meaning of the name Tamraparni, considered in itself, is 'The tree with sufficiently clear, but its application in this connexion is far from re being self-evident. Tamra means red, parni, from parna, a leaf, that which has leaves, that is, a tree. Tamraparni might therefore be expected to mean a tree with red leaves, but this is a strange derivation for the name of a river, and the idea naturally suggests itself that some event or legend capable of explaining the name lies beyond. It is especially worthy of notice that this very name was the oldest name for Ceylon. It was called Tambapanni by early Buddhists, three centimes before Christ, in king Asoka's inscription at Girnar, and when the Greeks first visited India in the time of Alexander the Great and began to inquire, with their usual zeal for knowledge, about India, the countries and peoples it contained, and the neighbouring countries, they ascertained the existence of a great adjacent island which they were told was called Taprobane — a mispronunciation of Tambapanni. Lanka, the beautiful island, is the name by which Ceylon Later names is called in Ramayana, & ordinarily in the Maha-wanso. of Cevlon.

Simhalam, however, is the name by which it was called by the later Buddhistic writers, from which came in regular succession the forms Sihalam, Silam, Selen-dib, Serendib, Zeelan, Ceylan, and Ceylon. [Dib is the Arabic survival of the Sanskrit dvipa, island.] From the form Silam comes the Tamil Ilam. Simha means a lion, Simhala the lion country, that is, either the country of the lion-slayers or more probably the country of the lion-like men. Tambapanni, or Tamraparni, as the name is more correctly written in Sanskrit, is said in the Maha-wanso to have been the name of the first settlement formed by Vijaya and his followers in Lanka, from which the name came to be applied to the whole Identity of island. This settlement seems to have been near Putlam on the western coast of Ceylon, nearly opposite the mouth of the chief river in Tinnevelly; and it may be regarded as certain that the two names had a common origin, one being derived from the other, like Boston in the United States and Boston in England. The name of the river may have been derived from the name of the settlement ; or vice versa, the name of the settlement may have been derived from the name of the river. The only question is, which use of the word was the earlier ? It may be supposed that a colony from the mouth of TamraparnI in Tinnevelly carried the name over with it to an earlier, settlement founded by it on the opposite coast of Ceylon. Or, on the other hand, after the Aryan adventurers under Vijaya settled in Ceylon, they may have formed a settlement on the Tinnevelly coast and given the chief river on the coast the name of the town from which they came. The general and natural course of migration would doubtless be from the mainland to the island ; but there may occasionally have been reflex waves of migration even in the earliest times, as there certainly were later on, traces of which survive in the existence in Tinnevelly and the western coast of castes whose traditions, and even in some instances, whose names, connect them with Ceylon. The marriage relations into which Vijaya and his followers are said to have entered with the Pandyas would also make them acquainted with Korkai at the mouth of the TamraparnI, the oldest capital of the Pandyas, which must have been their capital at that time, and the river may thus have been indebted for its name to those Singhalese visitors. At all events it seems more natural that TamraparnI, "the tree with the red loaves", should have been first the name of a tree, then of a town, then of a district, then of a river (it being not uncommon in India for villages to receive their names from remarkable trees), than that it should have been the name of a liver at the outset. Lassen interprets TamraparnI to mean " a tank with red lotuses," but this derivation seems to be quite unsupported. In Tamil poetical literature the first member of the compound is omitted and the river is called the Porunei, that is, the Parni, alone. The English sometimes erroneously write and pronounce the name as Tamrapoorney, but the error is derived from the old practice of writing the second part of the name Purni, instead of Parni.

The Greeks during the time of Ptolemy referred to the Tamraparni River as the "Solen." This is a remarkable fact, as for several centuries they had referred to Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka) as "Taprobane"—a name closely resembling that of the river. One would have expected them to use the same term, Taprobane, for the river as well.

This discrepancy suggests that "Tamraparni" may not have been the common name for the river when Greek merchants first arrived in Southern India. However, this theory does not align with its appearance in the Mahabharata—a text that predates Greek commercial contact with South India, which only began around the Christian era. There is no reason to believe that references to the river in the Mahabharata were later additions with sectarian intent. Furthermore, its mention in the Puranic geographical lists appears similarly neutral.

It seems likely, then, that while the Greeks referred to the river as "Solen," the local people—especially the Brahmins—continued to use the name "Tamraparni." How can this be explained? Historian Christian Lassen suggested that the river’s older name was "Sylaur," which he believed to be the name of a tributary. However, there is no historical evidence that the name "Sylaur" was ever in use.

This may be a misreading of "Sytaur"—a name by which the river was referred to by English officials as late as 1810. The confusion is likely due to a transcription error (mistaking "t" for "l"). The name is commonly written as "Chittaur," which corresponds to "Sittar" or "Chittar," meaning "the little river."

It is also clear that this tributary could not have been considered the main river, as it drains a much smaller portion of the hill country. The Greek word "Solen" has multiple meanings, one of which is a type of shellfish. In the absence of a better explanation, it is possible that the Greeks chose this name based on the word’s meaning in their own language.

Disclaimer: All posts are moderated and must cite original sources to maintain a respectful, informative space.

Copyright ©2025 - All Rights Reserved.

Designed & Developed with ❤️ Motherland Creators